The rape and murder of a Kolkata doctor in an Indian hospital

[ad_1]

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarly on Friday morning, a 31-year-old female doctor fell asleep in the lecture hall after a hard day at one of India’s oldest hospitals.

It was the last time he was seen alive.

The next morning, his colleagues found his naked body on the platform, with severe injuries. Later the police arrested a hospital volunteer in connection with this case which they say is a case of rape and murder in Kolkata, 138, RG Kar Medical College.

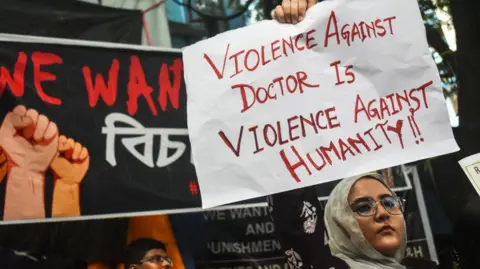

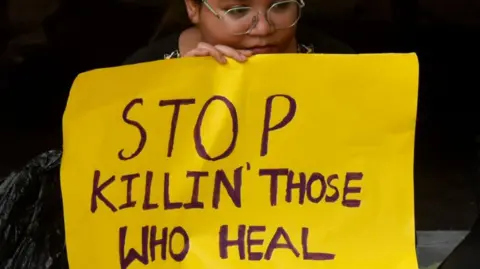

Angry doctors went on strike in the city and across India, demanding stricter legislation to protect health workers. This tragic incident has once again exposed the violence against health workers in this country.

Women do it for themselves about 30% of Indian doctors and 80% of the nursing staff. And they are more vulnerable than their male counterparts. Official data reveals the problem 4% increase in crimes against women by 2022, more than 20% of these incidents will involve rape and assault.

The crime at a Kolkata hospital last week has exposed the alarming security risks faced by many of India’s government-run health facilities.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt RG Kar Hospital, which sees more than 3,500 patients daily, overworked trainee doctors – some working up to 36 hours straight – had no designated rest rooms, forcing them to seek rest in the third-floor seminar room.

Reports indicate that the arrested suspect, a patient with a troubled past, was unable to enter the ward and was caught on CCTV. The police suspect that nothing was done about the volunteer.

“The hospital has always been our first home; we only go home to rest. We never thought it would be unsafe. Now, after this incident, we are afraid,” said Madhuparna Nandi, a junior doctor at Kolkata’s 76.-National Medical College.

Dr. Nandi’s own journey highlights how women doctors in India’s government hospitals have stopped working under conditions that threaten their safety.

In her hospital, where she resides in the field of gynecology and obstetrics, there are no designated rest rooms and separate toilets for female doctors.

“I use the toilets of patients or nurses if they allow me.” “When I work late, sometimes I sleep on an empty patient bed in the ward or in a cramped waiting room with a bed and a basin,” said Dr Nandi.

She says she feels unsafe even in the room she rests in after taking 24 hours, starting with outpatient work and continuing to the wards and maternity wards.

One night in 2021, during the outbreak of the Covid epidemic, some men entered his room and woke him up by touching him, saying, “Wake up, wake up. Look at our patient.”

“The incident disturbed me completely. But we never thought that it would come to a point where a doctor would be raped and killed in the hospital,” said Dr. Nandi.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat happened on Friday was not an isolated incident. The most shocking case is still this one Aruna Shanbauga nurse at a famous Mumbai hospital, who was left standing after being raped and strangled by a ward attendant in 1973. He died in 2015, after 42 years of severe brain damage and disability. Recently, in Kerala, Vandana Das, a 23-year-old medical trainee, was stabbed to death with surgical scissors by an intoxicated patient last year.

In overcrowded government hospitals, doctors often face anger from relatives of patients after death or because of urgent medical needs. Kamna Kakkar, an anesthesiologist, remembers a painful incident while working at night in the intensive care unit (ICU) during the 2021 violence at his hospital in Haryana, northern India.

“I was the only doctor in the ICU when three men, using the name of a politician, forced their way in looking for a highly controlled drug. I sacrificed myself to protect myself, knowing that the safety of my patients was at risk,” said Dr Kakkar.

Namrata Mitra, a Kolkata-based pathologist who studied at RG Kar Medical College, says her doctor father used to accompany her to work because she felt insecure.

Getty Images

Getty Images“When I was at work, I went with my father. Everyone laughed, but I had to sleep in a room closed off a long, dark corridor with a locked metal gate that could only be opened by a nurse when a patient came in,” Dr Mitra wrote on Facebook over the weekend.

“I’m not ashamed to admit that I was nervous. What if someone from the ward – a guard, or even a patient – tried something? I used the fact that my father was a doctor, but not everyone has that privilege.”

While working at a government health center in the state of West Bengal, Dr Mitra spent the night in a dilapidated one-story building that served as a doctor’s hostel.

“Since dusk, a group of boys gathered in the house, talking obscenities as we went in and out due to emergencies. “They were asking us to check their blood pressure as an excuse to contact us and they were looking through the windows of the broken toilets,” he wrote.

Years later, when I was working in an emergency room at a government hospital, “a group of drunken men passed by me, created noise, and one of them even groped me”, says Dr Mitra. “When I tried to complain, I found the police asleep with their guns.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThings have gotten worse over the years, said Saraswati Datta Bodhak, a pharmacist at a government hospital in West Bengal’s Banura district. “Both my daughters are junior doctors and they told me that hospital campuses in the province are full of anti-social people, drunkards and touts,” he said. Dr Bodhak remembers seeing a man with a gun walking around a top government hospital in Kolkata during a visit.

India does not have a strong law to protect health workers. Although 25 states have some anti-violence laws in place, convictions are “almost non-existent,” RV Asokan, president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), a doctors’ organization, told me. A 2015 survey by the IMA found that 75% of doctors in India have experienced some form of violence at work. “Safety in hospitals is almost non-existent,” he said. “One of the reasons is that no one thinks of hospitals as places of conflict.”

Some states like Haryana have installed private bouncers to beef up security in government hospitals. In 2022, the provincial government he called on states to send trained soldiers to critical hospitals, install CCTV cameras, set up rapid response teams, restrict entry to “undesirable people” and lodge complaints against violators. Not much happened, apparently.

Even the protesting doctors seem hopeless. “Nothing will change… The expectation will be for doctors to work round the clock and tolerate harassment as a matter of course,” said Dr Mitra. It’s a debilitating thought.

[ad_2]

Source link