The decline of birds of prey has resulted in the deaths of 500,000 people

[ad_1]

Getty Images

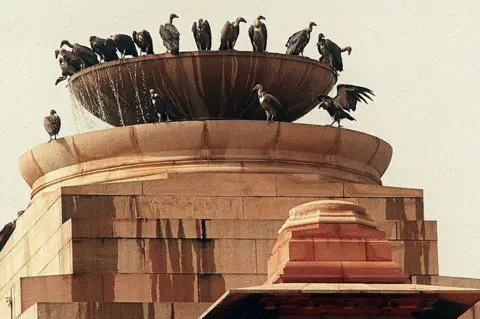

Getty ImagesLong ago, the vulture was an abundant and ubiquitous bird in India.

Birds of prey hovered over the scattered garbage dumps, looking for cattle carcasses. Sometimes they warned pilots about suction from jet engines during takeoff.

But more than two decades ago, vultures in India started dying because of a drug used to treat sick cattle.

By the mid-1990s, the population of 50 million vultures had been reduced to almost zero due to diclofenac, a cheap non-steroidal painkiller for cattle that kills vultures. The birds that ate the carcasses of animals treated with this drug had kidney attacks and died.

Since the 2006 ban on the use of animals diclofenac, the decline has decreased in some areas, but at least three species have lost a long time by 91-98%, according to the latest. State of India's Birds report.

And it doesn't stop there, according to a new peer-reviewed study. The unintended culling of these tough, predatory birds allowed deadly viruses and diseases to proliferate, leading to the deaths of up to half a million people a year within five years, a study published in the journal says. American Economic Association magazine.

AFP

AFP“Vultures are considered a natural sanitation service because of the important role they play in removing dead animals that contain bacteria and viruses from our environment – without them, diseases can spread,” said co-author of the study, Eyal Frank, assistant professor at the University. of Chicago's Harris School of Public Policy.

“Understanding the role vultures play in human life emphasizes the importance of protecting wild animals, not just the ones that look good and love to be petted. They all have a role to play in our ecosystem that affects our lives.”

Mr Frank and his co-author Anant Sudarshan compared mortality rates in India's vulture-rich regions with historically low vulture populations, before and after vulture declines. They also assessed sales of rabies vaccines, feral dog populations and pathogen levels in water.

They found that after sales of anti-inflammatory drugs increased and vulture populations declined, mortality rates increased by more than 4 percent in regions where the birds thrived.

The researchers also found that the effect was greater in urban areas with large livestock where dumping was common.

AFP

AFPThe authors estimate that between 2000 and 2005, the loss of vultures caused about 100,000 additional deaths per year, resulting in more than $69bn (£53bn) per year in human mortality or economic costs associated with premature death.

This death was caused by the spread of diseases and viruses that vultures could remove from the environment.

For example, without vultures, the number of stray dogs increases, which brings rabies to people.

Sales of rabies vaccines increased during that time but not enough. Unlike vultures, dogs were not efficient at cleaning up decaying waste, which led to bacteria and viruses spreading into drinking water through poor drainage and disposal methods. Bacteria in the water more than doubled.

“The fall of the vulture in India provides a stark example of the kind of irreversible and unpredictable costs to humans that can arise from the loss of a species,” said Mr Sudarshan, an associate professor at the University of Warwick. -study author.

Getty Images

Getty Images“In this case, new chemicals were to blame, but other human activities – habitat loss, wildlife trade, and now climate change – are affecting animals and, in turn, us. It is important to understand these costs and direct resources and regulations to the preservation of these keystone species in particular.”

Among India's vulture species, the white vulture, the Indian vulture and the red-headed vulture have experienced the largest long-term declines since the early 2000s, with populations declining by 98%, 95% and 91% respectively. The Egyptian vulture and the migratory griffon vulture have also declined significantly, but are not as catastrophic.

The 2019 livestock census in India recorded over 500 million animals, the highest number in the world. Vultures, highly efficient scavengers, have historically been relied upon by farmers to quickly remove livestock carcasses. The decline of vultures in India is the fastest ever recorded for a bird species and the largest since the extinction of the pigeon in the US, according to researchers.

India's remaining vultures are now concentrated in protected areas where their diet consists of more dead wildlife than potentially diseased livestock, according to the State of Indian Birds report. This continued decline suggests “continuing threats to vultures, which is of particular concern as the decline of vultures has had a negative impact on human well-being”.

Experts warn that veterinary drugs are still a major threat to donkeys. A decrease in the availability of carcasses, due to increased burials and competition from hunting dogs, exacerbates the problem. Quarrying and mining can disturb the nesting areas of some vulture species.

Will the vultures return? It's hard to say, although there are promising signs. Last year, 20 vultures – bred in captivity and fitted with satellite tags and rescued – released from a tiger reserve in West Bengal. More than 300 vultures have been recorded in this game recent survey in southern India. But more action is needed.

Follow BBC India on YouTube, Instagram, Twitter again Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link